The Money Creation project of the Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy (WRR) was intended to explore the possibilities of a public money system, with central bank money as a means of payment. Unfortunately, it has become a defense of the current system, rather than an exploration of the alternative.

In het kort

– The WRR states that a reform of the money system must go hand in hand with a solution to the debt problem.

– Improvements to the money system itself remain under‑exposed by this connection.

– The introduction of central bank digital currencies (CBDC) requires direction and will not lead to diversity.

The Money Creation project of the Netherlands Scientific Council for Government Policy (Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid, or “WRR”) is an important reference point in the debate on the need for radical reforms of the monetary system – including for us. In the report titled ‘Geld en Schuld: de publieke rol van banken’ (Money and debt: the public role of banks)(WRR, 2019), we are referred to as the “burgerinitiatief Virtueel Goud “ (Citizens’ initiative Virtual Gold). See box 1 for a brief sketch of our proposals (Van Hee and Wijngaard, 2016).

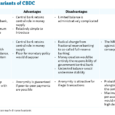

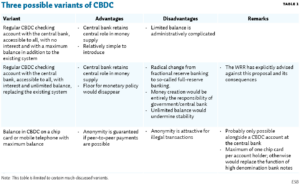

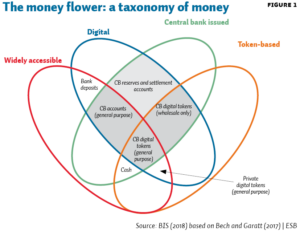

The report came about as a result of a motion in the Tweede Kamer (House of Representatives) , in which a request was made to the WRR for an opinion on the operation of the money system, including all forms of money creation by banks, which should at least involve the advantages and disadvantages of alternative systems.” It is about opposing the current system, where payments are made with claims on banks, on the one hand, and the alternatives (e.g. public money system), where payments are made with digital money issued by the central bank (central bank digital currency, CBDC) on the other hand. With this expectation the conclusion can only be that the report disappoints. It is a nice introduction to monetary economy, but not a balanced discussion of these two options.

The disappointment is mainly caused by the WRR focus on the relationship between money and debt. As a result of this focus, much attention is paid to secondary issues and the possibilities for improvement (such as debt problems or governance), but hardly to the fundamental shortcomings in the current payment system. Due to this lack of attention, the possibilities of the alternatives are not well explored and the report ultimately provides half-hearted advice with regard to the possibility of CBDC.

Misplaced attention to debt

In the debate on the proposals for a radically different monetary system, the focus is very much on debt, which diverts from the main problem – exploring the possibilities of the alternative and comparing it with the current payment system. We will take a closer look at company debts and household debts.

Debts to companies

There is much criticism of large debts, namely that they lead to instability. But is that criticism justified? The proponents of a public money system assume that those large debts and the fluctuations in them are system specific. If things go well, the value of investments grow and it becomes attractive to finance investments with debt – until the case turns, the so-called Minsky moment. They state that the bankers in the current system will always promote this debt formation, because of the short-term benefit that it brings. And that the current system offers too much room for this.

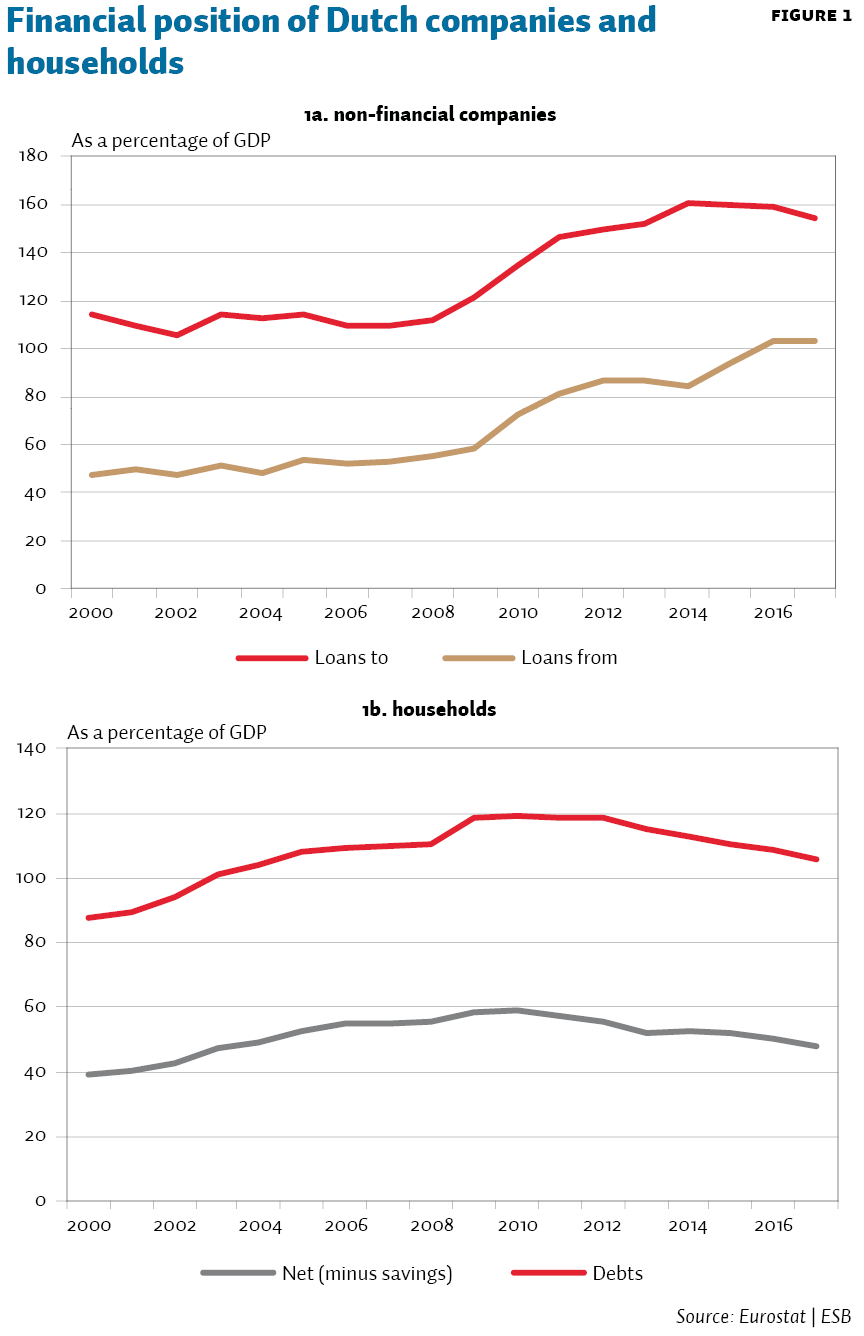

Opponents of radical change, including the writers of the WRR report, also share these concerns about debt development, but assume that measures can be taken to limit debt formation and thus counteract the seriousness of the consequences of the cycles . To reinforce the concern about the debt, the WRR provides pictures about the development of debt in the Netherlands and other countries (see Figure 4.1 of the report). For example, loans to companies as a percentage of the gross domestic product (Figure 1a).

They subsequently worry about that: “Very high, and even higher since the crisis started. Oops, we will have another crisis. Let us do something about those debts.” But these worries are exaggerated. The loans that the companies themselves have outstanding also have increased and the net loans are fairly stable. The low interest rates since the start of the crisis seem to have resulted in the search for more returns by issuing more credit themselves. If necessary, financed by taking on more debts themselves. We suspect that this mainly concerns mutual lending within the supply network of the companies. Then, the cause and effect are clear: crisis and low interest rates are the cause, and higher debts are the result. Tackling the debts is a strange remedy.

Household debts

The same story applies to households, but this mainly concerns mortgage debts; see figure 1b. As is known, those debts are high in the Netherlands. And mortgages are suspicious because they have contributed to the onset of the financial crisis. However, this mainly concerned American mortgages and the “cluttering” of them into unclear securitisations. How bad is this high Dutch mortgage debt actually?

Long-term house prices are rising. If a household can bear the interest and repayment, a mortgage is a good investment. The 2008 crisis caused major fluctuations in house prices and caused some houses to be “under water”. That, combined with both interest-only and top-rate mortgages that exceed the value of the property, is indeed unhealthy. But it gives a distorted picture when we consider the mortgage as a debt, and disregard the opposite value of the property, because one has to calculate using the net house capital (DNB, 2015).

The too easy provision of high mortgages contributes to fluctuations in house prices and therefore to fluctuations in consumer spending. But so do the increased activities of large investors in the housing market. This should then also have been taken into account – with attention being paid to the question of whether a starter is not better off paying a mortgage interest rather than a high rent. And the report already states that the mortgage issue cannot be viewed separately from the pension issue. It would therefore have been better not to put this point at the center of the debate on a different monetary system.

The fact that the term “debt” acts as a sort of stone on the road for the various parties in this debate is also related to the dogma “money = debt” adhered to by certain economists. See, for example, Boonstra (2015). Proponents of a full-reserve system (Positive Money (Jackson and Dyson, 2013), Ons Geld (Wortmann, 2017)), on the other hand, like to speak of “debt-free money”. The term “debt-free” and the “money = debt” dogma create unnecessary confusion. Fortunately, the report distances itself from this dogma. But in the meantime the debate about a different monetary system is stumbling over this.

The potential of the alternative

The current payment system is fragmented and extremely complicated, but it can be much simpler (box 1). For example, a PIN payment goes from a consumer to a company (five billion a year in our country) across many parties such as acquirers, issuers, payment facilitators and card schemes (for example Maestro or V PAY) and ultimately to the central bank for clearing and settlement. The WRR does not pay much attention to this, only section 4.1.1 discusses these objections in three pages.

Box 1 – Outline of the Virtual Gold proposal

The Virtual Gold proposal is based on a central digital payment system without cash.

There are several options for this, in the minimal variant the central system is only performing transactions as a clearing and settlement house. The system only remembers an encrypted fingerprint, made by the central system, of the last balance data of each account (amount, date, time). The account holder stores the encrypted balance data in his own digital wallet, which is in fact a proof of possession of money. Only the central system can create a new balance based on a transaction authorized by both account holders and based on the latest balance data from both account holders. The set of all wallets is in fact an extremely distributed ledger.

Such a system is simple, efficient and secure. All participants in payment transactions, including banks, are treated in the same way. However, banks and other financial service providers can easily offer their own services on top of this central payment system.

A cashless, central payment system offers new opportunities for monetary policy. Consider linking the balances on the payment accounts to a gross domestic product proxy. This stabilizes the purchasing power. With these new possibilities, monetary policy can be captured in simple rules.

It is disappointing that the WRR does not really address the question of whether the payment system could be simpler. We think that a system works better where everyone has access to a central bank account, with CBDC as normal payment method. Moreover, it disconnects financial services such as saving and lending from payments, which is wise.

Rather, the report is an apology: how can we adjust the current system here and there to make it acceptable again? With regard to a public money system based on CBDC , the report gives only a general description and is not going into the various variants. All kinds of warnings are then given: shadow money can arise, large debts can still arise, possible instability, etc. No options for improvement are discussed: how could you discourage the emergence of shadow money within such a system? What options are there with regard to monetary policy to prevent instability? This is unfortunate, because more is possible than what Positive Money (Jackson and Dyson, 2013) and Ons Geld (Wortmann, 2017) have suggested; see also our proposals (Van Hee and Wijngaard, 2017). Now it leads too easily to the conclusion that we should not drastically change the system. It is unknown territory, it is said. The WRR is right in that, of course, but it could have explored that territory too – then we would have known more.

Half-hearted advice on CBDC

Where a debate does not really start, you have to be careful when interpreting the conclusions. The possibility of making CBDC accessible to the public is very prudently supported in the WRR report.

The argument in favour for that is that it could contribute to the required diversity. It is expected that adding that option might have a healthy, disciplinary effect on lending. The WRR calls for more smaller banks and expects that this will contribute to stability and risk reduction in the current system.

That is a good idea for financing banks, but a bad idea for an efficient payment system. In the case of payment transactions you don’t want diversity at all, but just one system, because that is more efficient, more stable and more manageable. In addition to that one system, all kinds of private parties can then offer additional payment facilities and banks can develop lending. In this competition can be very healthy. But the basis must be centralized.

In short, if you want to introduce CBDC, you should not do that because you want diversity in the financial sector. Such half-hearted access to CBDC does not automatically grow into such a central system. You should not be happy with such a proposal – it is dead on arrival. If you accept such a half-hearted solution now, the principle of one central payment system would be corrupted.

References

Boonstra, W.W. (2015) Hoe werkt geldschepping? RaboResearch, available at economie.rabobank.com.

DNB (2015) De vermogensopbouw van huishoudens: is het beleid in balans? DNB Occasional Studies, 13-1.

Hee, Kees van, en J. Wijngaard (2016) Naar een nieuw monetair system met nieuw monetair beleid. White Paper Vaart-Dommel-Rotte Collectief, available at www.robuustgeld.nl.

Jackson, A. en B. Dyson (2013) Modernising money: why our monetary system is broken, and how to fix it. Positive Money.

Wortmann, E. (2017) Deliverage without a crunch. Working Paper Stichting Ons Geld, available at onsgeld.nu.

WRR (2019) Geld en schuld: de publieke rol van banken. WRR report, 100.