In many countries, the academic position of female economists is a very disadvantaged one – and to a far greater degree than is the case in the other social sciences. There seems to be no conclusive answer to the question why this is so, nor is it clear to what extent this also applies to the Netherlands. Is it because of their views on economic matters, because of their values, or has it to do with workplace practices?

Women in economics

Why is this article in English?

This article is part of our English publication ‘Women in Economics’. This dossier is in English because English is the main language of the economics and business faculties in the Netherlands, so an ESB dossier about the people who work there should be in English.

This article was originally published in Dutch in March 2018. The Dutch version can be found here.

In brief

– Half of the women employed at Dutch universities wish to leave academia.

– Women are often in positions where work and publication pressure are perceived to be highest.

– Female economists do not hold professional attitudes that are notably different than those held by men.

For years now at various levels within government pleas have been made to improve gender diversity within universities. Unfortunately, over all that time progress has remained limited. The percentage of female professors at Dutch universities is among the lowest in Europe, and compared with the various scientific fields in the Netherlands, economics has the lowest score with a mere ten percent (Rathenau, 2017). This is of course an improvement compared to the early nineties, when only two percent of the full professors within the science of economics were female. However the share still remains meagre. This perception is reinforced by looking at the last Economentop 40 in ESB (Lukkezen, 2017), which only included two women of in fact Belgian nationality. And a glance across the border informs us that other countries struggle with exactly the same problems (Jonung and Ståhlberg, 2008). So, all this raises the question why women in the economic sciences are lagging behind. Is the stance of women on economic subjects so radically different, or is their research quality so below par that there is not much demand for female professors? Or has the working environment in the economic sciences deteriorated to such an extent by the pressure to publish that women are looking for ‘healthier’ work?

In this article, I will – by means of a survey from 2015 among Dutch economists, jointly conducted with Arjo Klamer and Kees Koedijk – shed some light on these questions. This study will focus on female academics and solely scrutinize economists associated with Dutch universities. The proportion of women in the study is 23 percent (compare: in Van Dalen and Klamer (1996) this was 6 percent). In addition to this group of economists, the survey also included members of the Koninklijke Vereniging voor de Staathuishoudkunde (Royal Society for Political Economy), which has a broader composition of members particularly interested in the relation between policy and economy (Bijlsma and Van Dalen, 2016). All this had already been covered extensively in previous publications

(Van Dalen et al., 2015a; 2015b), and this more applied group will be excluded in the current study. However, the gender perspective has as yet not been investigated, although Van Dalen and Klamer (1998) also examined the divergencies between male and female economists in the past. When doing so in 1995, the insights and opinions of the relatively small group of women present at the time were not found to be discernibly different. However, since then, a lot has changed at Dutch universities and it is worthwhile to take another closer look at the differences between men and women in the sciences.

Different views

The most basic question is whether women have different views on economics as a science compared to men, which possibly made them feel uncomfortable with this field. Yet in listing the survey results, we do see that the differences here are again marginal. Whether one enquires about the success factors in becoming an economist, or opinions on economic policy and methodological principles, one may roughly speaking say that in the field of economics men and women do not differ substantially from one another.

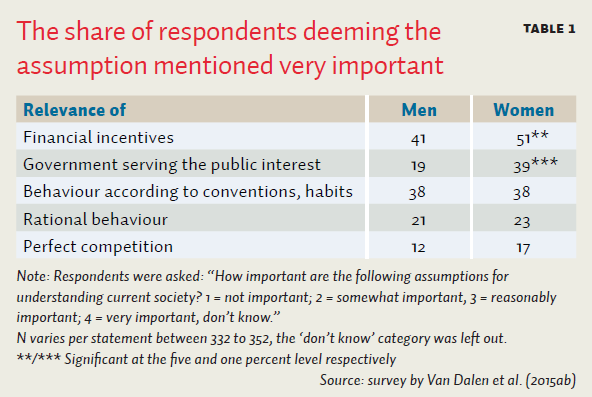

Table 1 illustrates the comparison of men and women when questioned as to the importance of certain assumptions in understanding our present-day society. Rationality or perfect competition are not considered highly important, although women find this slighly more important. Yet both men and women find financial incentives very important. But the point on which women clearly differ from men (and significantly so), is the notion that governments serve the public interest. Women are far more convinced than men that this is an accurate assumption of how society works.

We have also inquired about the factors that make an academic economist successful, and as to all of these factors both men and women again reacted reasonably similarly. The only nuance, however, is that women perceive far more strongly than men that, in achieving success, a prominent part is played by both the networking with eminent scholars (72 percent considers this very important, vis-à-vis 56 percent of the men) and the acquiring of research funds (71 percent considers this to play a major part, compared to 57 percent of the men). However, that does not imply that they therefore pursue such success en masse. When asked about their ambitions, women appear to be slightly less eager to work their way to the top. The statement “Being cited and respected by other colleagues is the main motivation to my work” is rejected by 47 percent of the women (compared to 33 percent of the men). Only 29 percent of the women strongly agree with this statement (compared to 40 percent of the men). In short, citations or rankings do not have the same stimulating effect on women as they appear to have on men.

When asked about the economists they respect, Kahneman is mentioned most frequently (eight times), followed by Sen, Acemoglu and Krugman (each six times). Among the men, these names – with the exception of Sen – are also frequently mentioned, and although Keynes (41 votes) is the most respected one here, hardly any women mention him. It is also remarkable that women don’t mention any female economists or hardly any, even though a woman – Elinor Ostrom – has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Economics. Apparently, there are still no outstanding female role models.

Obviously, when considering all these differences, it should be noted that gender issues have not been explicitly addressed in this survey. It is fairly obvious that men and women are likely to have widely differing views on these issues. For instance, May et al. (2018) show such differences to exist among European academic economists. However, when they examine economic issues they do show that women are less convinced of the effectiveness of market solutions than men are, and more frequently in favour of government intervention. The latter finding is related to the aforementioned observation that women have more confidence in the notion that governments serve the general interest.

Different values

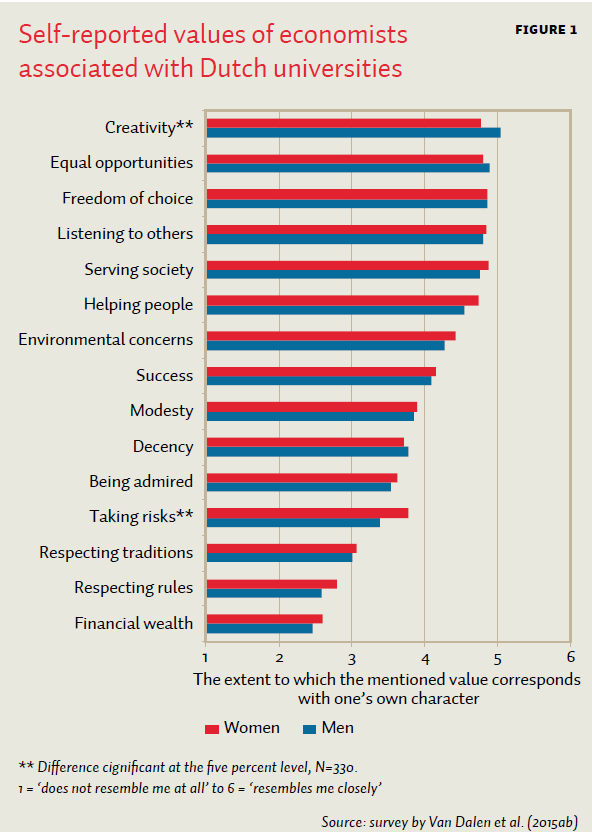

The divergencies between men and women as to the way they perceive their profession can be observed, but these are not so marked that we can rightfully speak of two totally different worlds. The question then arises whether female economists have different values in everyday life compared to those of male economists. To establish this, the respondents answered questions – also used by Schwartz et al. (2012) and in the European Social Survey – in order to ascertain what the individuals’ personal values were. Figure 1 charts the extent to which male and female economists at Dutch universities differ from each other in this regard.

These differences turn out to be very minute. The only two values that differ statistically significantly from each other are ‘creativity (being innovative)’ and ‘taking risks’. Men consider themselves more creative than women, and women find that taking risks (seeking adventure) fits in with their character more than with that of men. However, upon close scrutiny of the figure we see that even as to these personal values crucial within science – like creativity and taking risks – men and women do not differ greatly from one another.

Difference in work pressure

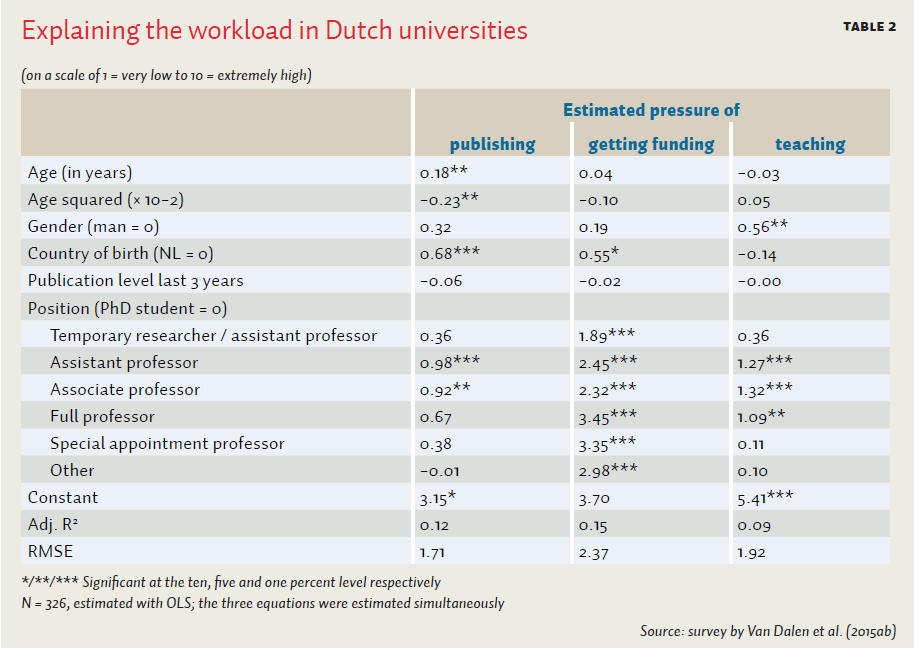

The data thus suggest that men and women do not live in totally different worlds. But a different picture emerges if we look at working conditions. In Van Dalen et al. (2015a), workload was briefly referred to as a potential explanation. Here, on a number of points, there are indeed some remarkable differences between men and women. The most striking one is dissatisfaction about work pressure: fifty percent of the female economists working at a university consider leaving academia because of the publication pressure. For men the percentage is considerably lower, to wit 29 percent. Such dissatisfaction is well corroborated: 49 percent of the women describe the publication pressure as extremely high (9 or 10 on a 10-point scale), while among men only 31 percent characterizes it as extreme. Are women then unable to cope with the competitive pressures of academia? This conclusion seems premature. The current cross-sectional data sample does not allow us to track economists over time, but we can explain part of this difference by analyzing the workload in more detail. Table 2 contains an analysis of the perceived workload with respect to publishing, acquiring research funds and teaching.

Publication pressure has a distinct age profile, with the pressure at its peak during an academic’s mid-30s – corresponding with the fact that the pressure is mainly felt at an assistant professor and associate professor level. The latter is probably related to the phenomenon of tenure-track jobs. Employees are de facto only eligible for a permanent position once they have met certain requirements, particularly regarding publications in high-quality journals. It is an up or out-system. And so this pressure actually applies to everyone close to obtaining a full professorship. However, it should be noted that being female (see the estimates’ first column) does not exert any influence on publication pressure.

Foreigners experience additional pressure in the publish-or-perish culture of universities, and it should be noted that 35 percent of the women in the sample were born abroad (compared to 15 percent of the men). It remains somewhat of a puzzle why publication pressure among foreigners is perceived to be higher. It is possible that in the Netherlands the pressure is higher than elsewhere in Europe or the world. Or it may simply have to do with the fact that foreign staff members who do not succeed in academia, have few fallback options to resort to in the Dutch labour market. Or perhaps foreigners are more ambitious to work at top universities in the US or UK, and realize that those who do not publish at a certain level will not reach the Ivy League. Finally, it is remarkable that the publication track record does not really leave its mark on the workload perceived – whether you publish a lot or little, the pressure to publish remains the same. In the economic sciences, you are only as good as your last publication, and there is no time for slacking.

The only gender effect on work pressure is to be found in teaching. However, it also remains unclear why women perceive this pressure as higher than men do. It may be that women impose more stringent standards upon themselves when teaching, or feel that they need to exert more effort regarding this point than men would. In itself, this is not a strange assumption. Research shows, for example, that women spend more time than men on making their papers ‘readable’, and that at tenure decisions women get insufficient recognition for jointly written papers. In fact, when women write together with men, the credit mainly goes to the man (Sarsons, 2017). This is one of the invisible factors seeing to it that, as a woman, one has to make an extra effort in order to be acknowledged in academia.

Conclusions

In the Netherlands, women in economics are no longer as rare as twenty or thirty years ago. Nevertheless, among the current staff women are still clearly a minority, and certainly among full professors a woman is an exception. As far as the survey data among Dutch economists show, there are no huge differences between men and women. This suggests that in everyday practice, forces are at play that are harder to measure.

Competitiveness

For instance, Van Damme (2014) states that women are less competitive, and in the literature (Bertrand, 2011) this is also presented as a reasonably robust finding. One could regard getting one’s work published in top journals as being ‘all in the academic game’ – yet according to the pertaining studies women find the pressure of this far too high and also a lot higher than men do. In addition, women are less susceptible to the buzz of being cited. And the fact that they engage less in this ‘struggle’ is not a finding reserved to the economic sciences. The pressure to publish, and the associated competitive pressure in the academic world, can create an unhealthy working environment in which the danger of a burnout lurks just around the corner (Levecque et al., 2017; Tijdink et al., 2013). Still, the fact that, within the spectrum of the sciences, economics scores lowest in terms of appointing women does demand additional explanation.

Customs

In a recent interview, the Princeton economist Anne Case points out a number of factors, but also refers to the tacit codes of conduct among economists collaborating in the workplace. The culture is, in comparison with other social sciences, more aggressive and characterised by a strong urge to prove oneself – which necessitates a fiercer jockeying for your position. For example, as to economics seminars she comments: “Presenting your latest findings can feel more like a testimony in front of a firing squad than a collaborative space where other experts help you sharpen your research” (Quartz, 2017). And competition at the expense of others is something that goes down badly with women and really puts them off. Whatever the case may be, there is something the matter with the world of economics. And the fact that half of the women wish to leave academia due to the publication pressure should be taken as ‘the writing on the wall’.

References

Bertrand, M. (2011) New perspectives on gender. In: O. Ashenfelter en D. Card (ed.), Handbook of Labor Economics, Vol. 4, Part B. Amsterdam: North Holland, 1545–1592.

Bijlsma, M. and H.P. van Dalen (2016) De Nederlandse club van politieke economen. ESB, 101(4726), 66–69.

Dalen, H.P. van, and A. Klamer (1996) Telgen van Tinbergen: het verhaal van de Nederlandse econoom. Amsterdam: Balans.

Dalen, H.P. van, and A. Klamer (1998) Vrouwelijke economen in Nederland: een klasse apart? Tijdschrift voor Politieke Economie, 20(3), 37–58.

Dalen, H.P., A. Klamer and K. Koedijk (2015a) De econoom als onrustzaaier en bestrijder van de status quo. Article at www.mejudice.nl, June 23.

Dalen, H.P., A. Klamer and K. Koedijk (2015b) De ideale econoom staat onder druk. Article at www.mejudice.nl, September 16.

Damme, E.E.C. van (2014) Economie als menswetenschap. ESB, 99(4693), 557.

Jonung, C. and A.C. Ståhlberg (2008) Reaching the top? On gender balance in the economics profession. Econ Journal Watch, 5(2), 174–192.

Levecque, K., F. Anseel, A. De Beuckelaer et al. (2017) Work organization and mental health problems in PhD students. Research Policy, 46(4), 868–879.

Lukkezen, J. (2017) Economentop 40. ESB, 102(4756), 589–591.

May, A.M., M.G. McGarvey and D. Kucera (2018) Gender and European economic policy: a survey of the views of European economists on contemporary economic policy. Kyklos, 71(1), 162–183.

Quartz (2017) A Princeton economist has a theory for why there are so few women in economics. Article at qz.com, December 27.

Rathenau (2017) Het aandeel vrouwelijke hoogleraren in Nederland en EU-landen. Article at www.rathenau.nl.

Sarsons, H. (2017) Gender differences in recognition for group work. Working Paper, Harvard University.

Schwartz, S.H., J. Cieciuch, M. Vecchione et al. (2012) Refining the theory of basic individual values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(4), 663–688.

Tijdink, J.K., A.C. Vergouwen and Y.M. Smulders (2013) Publication pressure and burn out among Dutch medical professors: a nationwide survey. PLoS One, 8(9), e73381.

Auteur

Categorieën