Compared to other scientific disciplines, academics in economics and business stress the importance of stereotypical masculine traits like self-confidence and competitiveness for career success. Feminine traits like cooperativeness and modesty are deemed less important. Could this explain the low number of female academics in economics and business?

Women in economics

Why is this article in English?

This article is part of our English publication ‘Women in Economics’. This dossier is in English because English is the main language of the economics and business faculties in the Netherlands, so an ESB dossier about the people who work there should be in English.

In brief

– Economists have a relatively masculine image of how they should behave in order to achieve career success.

– Female economist report a large difference between the masculinity needed to succeed and their own masculinity.

– A highly masculine occupational stereotype is a ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’ that perpetuates the underrepresentation of women.

Although it is well-known that women are vastly underrepresented in natural sciences and technology, the representation of women in the economics and business departments at Dutch universities is even lower, with 10.4 percent female professors in 2016. As argued by Teunissen and Hogendoorn (2018) the scarcity of women, and the lack of inclusion of the female-scholar perspective has negative consequences for the quality of economic research, as well as for the socio-economic policy based on this research. We here argue that, in economics, one important obstacle to female academics’ career progression is the very masculine stereotype as to what it means to be successful within this discipline.

Research shows that people associate divergent roles and characteristics with men and with women (Eagly and Karau, 2002). Women are stereotypically associated with communal roles (for instance, mother, nurse) and with traits like being modest, cooperative and caring. Men, on the other hand, are associated more explicitly with agentic roles (for instance leaders, managers) and characteristics like self-interest, self-confidence and competitiveness. People’s perceptions of the characteristics necessary to be successful in certain occupations are strongly influenced by how men and women within that occupation are represented. As regards occupations that are dominated by men, people are likely to assume that there stereotypically male traits are necessary to be successful, while stereotypically feminine traits are seen as irrelevant or even counterproductive (Heilman and Caleo, 2018). Given the overrepresentation of men in economics and business departments, particularly at the associate and fullprofessor level, we expect that the occupational stereotype will be a distinctly masculine one, compared to the scientific disciplines in which women are more abundantly represented, such as the humanities and behavioural sciences.

Another indication that the occupational stereotype in economics and business is dominated by masculine rather than feminine traits, is that students tend to score particularly high on stereotypically masculine traits and low on stereotypically feminine ones. Economics and business students behave more selfishly, competitively and less prosocially than psychology students do (Van Lange et al., 2011), are less charitable and generous than arts and sciences majors (Bauman and Rose, 2011), and more likely than other students to favour efficiency and profit-maximizing over fairness and social considerations (Cipriani et al., 2009). Furthermore, they are less likely to show trust and trustworthy behaviour than for instance law students (Haucap and Müller, 2014). These differences between economics and business students and students from other disciplines are thought to be due to both effects of selection and of learning. Exposure to concepts like Rational Economic Man, the Invisible Hand and Standard Economics’ assumptions of selfishness and rationality may have changed their behaviour and created cynicism about the prosocial motivations of others (Gerlach, 2017).

Economics as a Masculine field

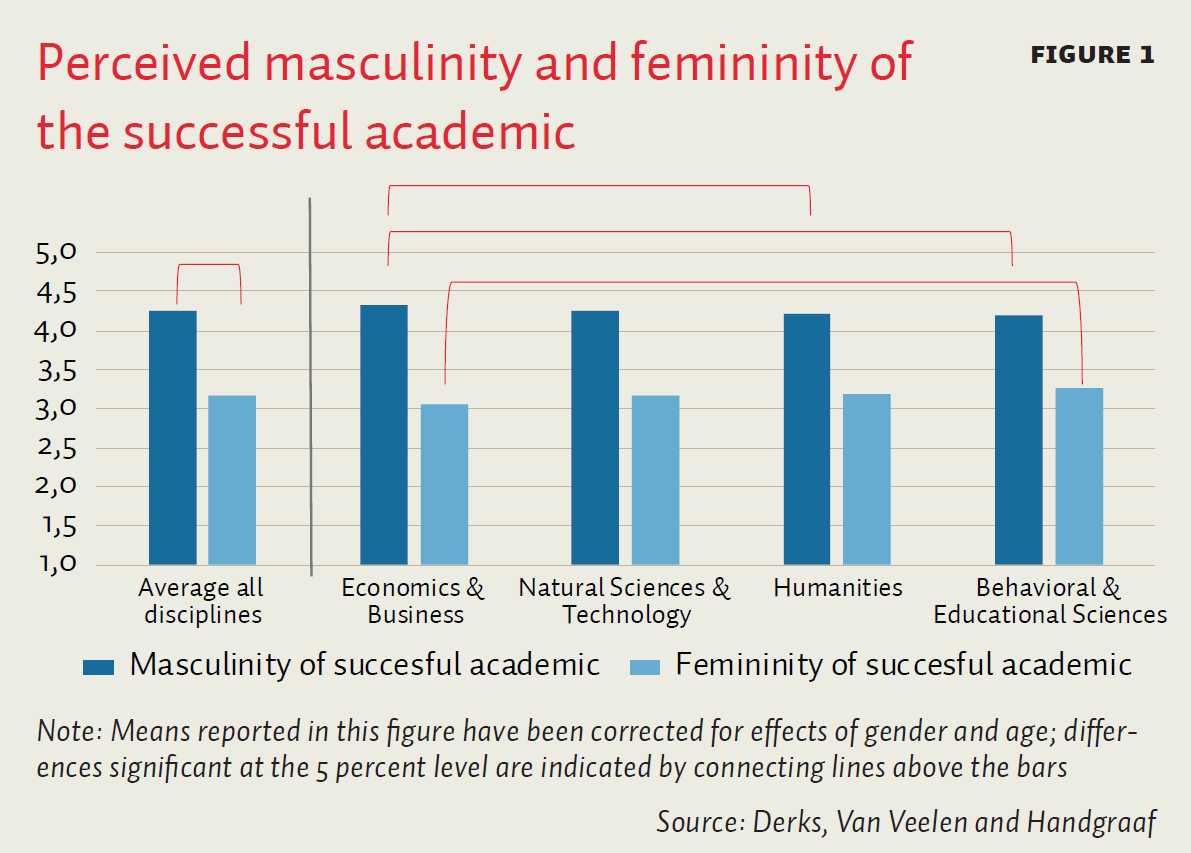

In order to answer the question whether economics is a particularly masculine field, we compared the occupational stereotype in economics and business with that in other disciplines. We used data from an online questionnaire that was administered during the 2017/2018 academic year among 2,256 academics who worked as assistant (50.7 percent), associate (22.2 percent) or full professors (27.1 percent) at the fourteen Dutch universities. We focused on scholars working in economics and business (N = 440; 26 percent women), and compared their perceptions of occupational stereotypes with those of scholars in natural sciences and technology, where women are underrepresented to a similar degree (N = 949; 22 percent women), and also with two disciplines in which there is a more equal representation of men and women, that is the humanities (N = 685; 46 percent women) and behavioural and educational sciences (N = 482; 64 percent women).

Occupational stereotypes were measured by having respondents rate their image of the successful academic within their own discipline as to stereotypically masculine and feminine traits (Bem, 1974). Masculinity was assessed according to the following characteristics: being performance-oriented, focusing on one’s own scientific output, wanting to be the best, being a good networker, being assertive and being self-confident. Femininity was assessed as to being a good collaborator, a nice colleague, helpful, loyal, modest, spending a lot of time on teaching, contributing to a good working atmosphere and being concerned with other colleagues. In addition, respondents were asked to also rate themselves on these masculine and feminine traits.

Academics across the scientific disciplines reported that the prototypical successful scientist was more explicitly masculine than feminine (Figure 1). Data also showed that, across disciplines, women reported an even more masculine prototype than men (4.32 for women versus 4.19 for men). Interesting was that the discipline showing the most masculine and least feminine occupational stereotype was economics and business, although differences were small. This highly masculine prototype was comparable to the prototype reported in natural sciences and technology. However, in comparison to economics and business, the scientist’s prototype was significantly less masculine in the humanities and the behavioural and educational sciences. Moreover, the prototype of the successful academic was significantly less feminine in economics and business, when compared with the behavioural and educational sciences.

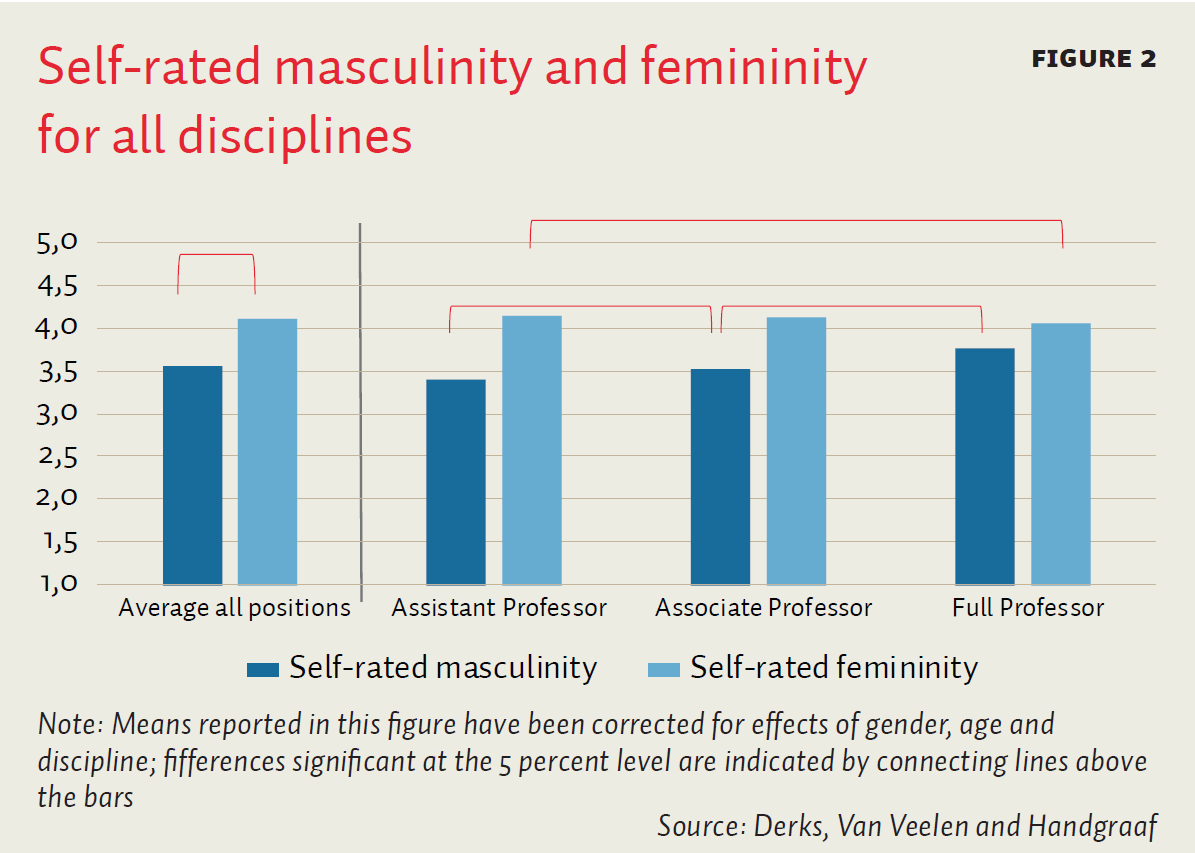

It is important to emphasize that there were no differences between how male and female academics rated themselves as to masculinity and femininity. Remarkably, in all disciplines, both men and women rated themselves as being more feminine than masculine (Figure 2). This suggests that most people working in academia think that, in order to fit in with the successful academic’s stereotype, they should become more masculine and less feminine.

And they would be right in their conclusion. As depicted in Figure 2, results showed that full professors reported themselves to be more masculine and less feminine than assistant and associate professors. So, the fact that academics who have reached the highest positions in academia indeed consider themselves the most masculine and least feminine of all academics is probably due to selection effects (academics who fit better into the masculine prototype are more likely to stay in academia and to receive promotion) as well as to socialization effects (as academics climb up in the hierarchy, they adjust to the highly masculine prototype; an effect that is in line with the queen-bee phenomenon).

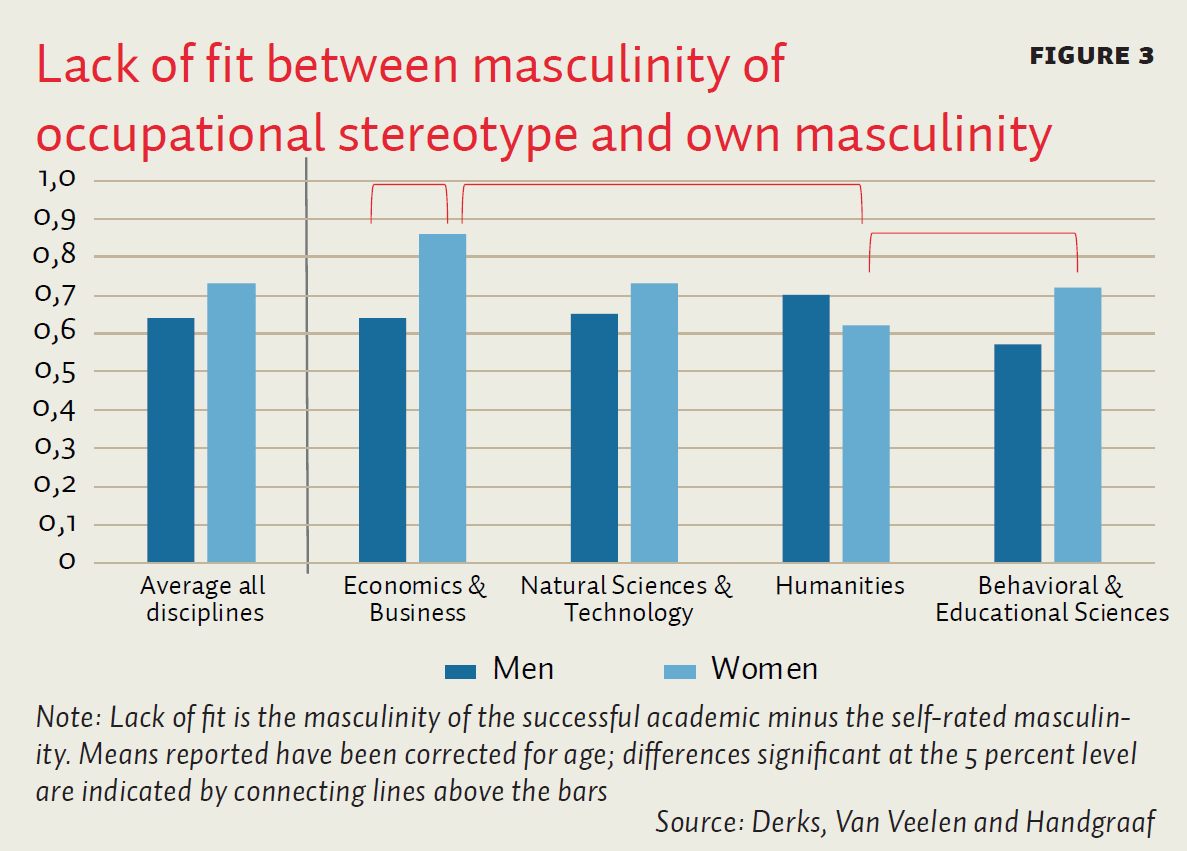

Finally, although both men and women in academia reported a lack of fit between how masculine they are and how masculine they need to be in order to be successful in academia (Figure 3), there was only one discipline where the lack of fit was greater for women than for men: economics and business. Moreover, whereas men’s lack of fit did not depend on the discipline they worked in, women in economics and business reported a greater lack of fit than the women in the humanities did.

Box 1: Male occupational stereotypes limit women’s opportunities

When occupational stereotypes emphasize masculinity rather than femininity, this lowers the possibilities for women to succeed in at least three ways:

1. Highly masculine occupational stereotypes trigger bias in the evaluation of women’s competence (Eagly and Karau, 2002). We simply do not expect women to have what it takes in order to be as successful as men in masculine occupations. Therefore masculine stereotypes create a systematic bias when perceiving the competence of women. On top of this, even if women discomfirm gender stereotypes by showing determination and irrefutable competence in masculine spheres, they experience a backlash in the form of social and economic penalties. Agentic women face a ‘dominance penalty’ (Rudman and Phelan, 2008): People – men and women alike – tend to dislike women who transgress the norm that a woman should be nice and sociable, and so they are less likely to hire agentic women who are comparable to agentic men. As a result, in masculine occupations, ambitious women have to walk a tightrope between being too masculine and therefore disliked, and being too feminine and therefore perceived as not competent enough.

2. Related to the first point, masculine occupational stereotypes create lack of fit between the general expectations we have of women, and the stereotypically masculine requirements for occupational success. This lack of fit works as a self-fulfilling prophecy, so that women themselves tend to expect that they will not succeed (Heilman, 2012). When women sense that they are not masculine enough to be successful, this lowers their occupational identification and increases turnover intentions (Peters et al., 2012).

3. When organizations have a strong focus on masculinity, this may undermine the solidarity among the women working there. We tend to assume that women who are successful in masculine organizations will help other women to achieve the same as they do and are motivated to actively disconfirm gender stereotypes. However, research on the ‘queen-bee phenomenon’ shows that highly masculine work settings motivate some women to try to fit in with this culture by stressing how different they are to other women (for example more competent and committed than other women) and that they show high masculinity themselves (Derks et al., 2016). As a result, the few women breaking through the glass ceiling are often just as unwilling as their male colleagues are to promote opportunities for junior women (Faniko et al., 2017).

Conclusion

We present evidence to show that, though in general academia forms a masculine work setting, economics and business is perceived as being an even a more masculine discipline. The prototypical successful economics scholar has a high score on stereotypically masculine traits, such as self-confidence, self-interest and assertiveness, rather than on collaboration and being a nice colleague. Although this image of substantial masculinity is clearly obvious in all of the scientific disciplines studied here, it was particularly marked in economics and business and the natural sciences, as compared to the humanities and the behavioural and educational sciences. The literature we reviewed (Box 1) suggests that the masculine stereotype is not only a result of the scarce representation of women in economics and business. In fact, it also reinforces the female underrepresentation in economics as this masculine image triggers gender bias, discouraging women to pursue an economics career and even motivating those who do enter to conform to the highly masculine culture rather than challenge it.

Although changing the excessively masculine occupational stereotype in economics and business will be difficult, there are things that could indeed help to change this masculine image. As people base stereotypes on the examples they see, a significant increase in the number of female professors will in the long run affect the prototypical image academics have of the successful economist, allowing for more feminine traits to be included in it. Moreover, by more explicitly rewarding stereotypically feminine qualities in performance evaluations – qualities like being a team player who focuses on team science rather than on individual publications – economics and business departments can change the perception that academic success depends on masculine rather than feminine traits. By actively diversifying the perception of what it takes to be successful towards a more inclusive image, incorporating both feminine and masculine qualities, it is possible to breach the self-perpetuating mechanisms that preserve female underrepresentation. This will encourage a greater number of women to enter, succeed and have their impact on the discipline of economics.

References

Bauman, Y. and E. Rose (2011) Selection or indoctrination: why do economics students donate less than the rest? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 79(3), 318–327.

Bem, S.L. (1974) The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 155–162.

Cipriani, G.P., D. Lubian and A. Zago (2009) Natural born economists? Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(3), 455–468.

Derks, B., C. van Laar and N. Ellemers (2016) The queen bee phenomenon: why women leaders distance themselves from junior women. The Leadership Quarterly, 27(3), 456–469.

Eagly, A.H. and S.J. Karau (2002) Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598.

Faniko, K., N. Ellemers, B. Derks and F. Lorenzi-Cioldi (2017) Nothing changes, really: why women who break through the glass ceiling end up reinforcing it. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(5), 638–651.

Gerlach, P. (2017) The games economists play: why economics students behave more selfishly than other students. PloS one, 12(9), e0183814.

Haucap, J. and A. Müller (2014) Why are economists so different? Nature, nurture and gender effects in a simple trust game. DICE Discussion Paper, 136.

Heilman, M.E. (2012) Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 113–135.

Heilman, M.E. and S. Caleo (2018) Combatting gender discrimination: a lack of fit framework. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 21(5), 725–744.

Lange, P.A. van, M. Schippers and D. Balliet (2011) Who volunteers in psychology experiments? An empirical review of prosocial motivation in volunteering. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(3), 279–284.

Peters, K., M.K. Ryan, S.A. Haslam and H. Fernandes (2012) To belong or not to belong: evidence that women’s occupational disidentification is promoted by lack of fit with masculine occupational prototypes. Journal of Personnel Psychology, 11(3), 148–158.

Rudman, L.A. and J.E. Phelan (2008) Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 61–79.

Teunissen, S. and C. Hogendoorn (2018) Weinig vrouwen in het economisch debat. ESB, 19 maart 2018.

Auteurs

Categorieën