The gender imbalance in economics does not only make a fascinating research topic, it is also highly personal for many researchers. In a round table discussion we asked both female and male economists to share their views.

Women in economics

Why is this article in English?

This article is part of our English publication ‘Women in Economics’. This dossier is in English because English is the main language of the economics and business faculties in the Netherlands, so an ESB dossier about the people who work there should be in English.

Participants in the discussion

Teresa Bago d’Uva: Erasmus University Rotterdam

Wike Been: University of Amsterdam

Anne Boring: Erasmus University Rotterdam

Thomas Buser: University of Amsterdam

Diogo Geraldes: Utrecht University

Carla Haelermans: Maastricht University

Max van Lent: Leiden University

Jasper Lukkezen: ESB, moderator

Anna Minasyan: University of Groningen

Karlijn Morsink: Utrecht University

Sobana Sheikh Rashid: ESB

Christina Rott: VU University Amsterdam

Trudie Schils: Maastricht University

Sylvia Teunissen: Ministry of Finance

Elisa de Weerd: ESB

“I notice that we are leaving out personal experience when introducing ourselves, but I think it is relevant that I have three young children.” In the C.W. Opzoomerkamer in the academic building of Utrecht University, surrounded by portraits of male academics, researchers are discussing their experiences with the gender imbalance in the field of economics. The attendees are academics from seven Dutch universities who have responded to the invitation of ESB. During the discussion, the researchers are asked to share their perceptions on the causes and consequences of the low number of female professors in economics. The biases embedded in the workplace as well as personal preferences and experiences are considered. The discussion was held under the Chatham House Rule. So, the opinions in this article may not necessarily reflect the opinion of every individual participant.

The issue

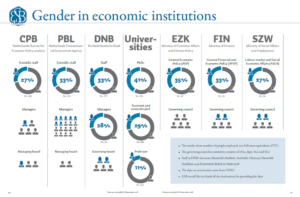

Somehow, female economists do not feel encouraged to continue in this field. Even though the low percentage of women is an issue within academics in general, the gender imbalance is relatively strong in the economics domain. However, across the economics field the gender imbalance also varies. The gender imbalance is smaller in more social economics fields. Attendees feel that it is implicitly thought that women do the ‘easier’ social research, the ‘fluffy stuff’, and that men do the ‘hard’ quantitative analyses. Strikingly, the majority of the researchers participating in the discussion, both female and male, are working on the fluffy stuff.

According to the attendees, the low number of female professors in economics is clearly an issue. As there is no intrinsic reason why women should be worse economists than men, this low number of female economists in academia suggests that we are not using talent as we should. Other consequences of the imbalance are that certain research areas may be underrepresented in the field, and that intolerance towards flexible hours may continue to exist.

Tenure track system

An overly competitive culture is experienced in economics which is less the case in other fields. This is for instance reflected in an ‘extreme obsession’ with prestige and rankings. It is relatively common for economics faculties to have a tenure track system. This allows universities to attract talented researchers by using a strict selection process. On the one hand, this provides researchers with a clear career path. Once this path has been followed, there is the prospect of many years of employment. On the other hand, this system is based on ‘up or out’. If the criteria are not met, the staff member will have to look for a position elsewhere. There is a focus on publication in top journals, and the extreme competitiveness can make this very challenging. This strict selection process in itself may already increase the gender imbalance, as women may be less inclined to face this competition.

It is only very recently that extensions regarding the tenure track period for pregnancies are being taken into account. Although some participants feel that this is a big improvement, others receive this optimistic view with sarcastic laughter, while emphasizing that, so far, only very small ‘improvements’ have been made. Furthermore, increasing opportunities to ‘stop the clock’ during the tenure track do not guarantee an improvement in the gender imbalance. Allowing both men and women to stop the clock when having a child, may even increase tenure rates for male staff, and reduce them for female staff (Antecol et al., 2018). This suggests that the policies do not compensate for the productivity challenges that women face after childbirth. Despite this increased divergence, stop-the-clock policies do not decrease women’s tenure rates during their overall career.

Because the tenure track period is likely to coincide with the child-bearing period, women may feel that it is impossible to meet those strict criteria as long as they are not adjusted. Entering a tenure track system requires a researcher to sacrifice a lot for what is an insecure future. As women generally have to face choices about having children slightly earlier than men, this may even lead to self-selection out of an academic career in economics.

Moreover, compared to other disciplines, in economics it is not that common to have a career in research. There is a long list of alternative career paths, which may make a career in academia less attractive. Combined with other characteristics of the field discussed in this article, when women face choices about entering a tenure track, they may be more inclined to choose other career paths compared to researchers in other disciplines.

Aggressive culture

Furthermore, researchers face an aggressive culture in the field of economics. Regardless of whether this is experienced as an issue or not, it is seen as something that distinguishes economics from other disciplines. Participants are especially critical of the aggressive manner in which criticism is voiced. A male participant explains that he sees participating in heated discussions during seminars and classes as a sport, but that others may perceive it as demeaning. “How to get humiliated in front of an audience” can be regarded as a skill that is part of the job. Women often take feedback more personally, and can suffer more under those harsh comments than men do. Furthermore, some attendees experience that women may actually be getting more negative feedback than men. Women may also be more likely to show how they feel about feedback. “Maybe men are also scared, but don’t tell you so.” This highly critical culture is sometimes also encouraged by mentors or colleagues. If you can’t handle it, you’re out.

Single-authored work

While in other disciplines it is completely acceptable to have a large team of authors, in economics there is a higher focus on single-authored work or small teams, especially when one is entering the job market. Contributing to another researcher’s work by, for instance, gathering data does not guarantee co-authorship, and thus a return for this effort is not assured. In general, it is often the female researchers who take this kind of work upon them. Additionally, women become less likely to receive tenure when they have more co-authors, to a greater extent than men (Sarsons, 2017). In economics, co-authors are listed in alphabetical order rather than in order of contribution. This may also influence the incentive to contribute to other people’s work, because putting more effort in a research project is not reflected in this order, while in other disciplines this would be the case. In general, women enjoy cooperation, and the insecurity of recognition for this may also discourage female staff to pursue a career in economics research. Taking into account that these papers also need to be published in top journals, the time it takes to write and publish such a good paper is relatively long in economics.

Aspirations

Reasons frequently mentioned for female staff quitting their academic career path are due to the fact that, next to their research, women aspire to other things in life. Having a family, maintaining a relationship, or engaging in societal impact activities – all of these take time and are generally not well-facilitated. “I have a female colleague who has literally been told that she is an idiot getting pregnant at this stage of her career.” Working fifty hours a week in order to meet the standard is not uncommon, and if one also takes into account teaching obligations this does not leave much time for other activities. Because of the highly competitive culture in economics, this effect may be larger in economics than elsewhere. One way to deal with this would be to facilitate support for it so that researchers can mainly focus on their core tasks, for instance by providing daycare or by making working from home possible. However, this also has its downsides. Providing these facilities may encourage the idea that working such long hours is what can you can expect if you want to make a career in economics research.

Mentoring

The participants point out that a lot of support and information can be provided by mentors. There are strict and unwritten rules in economics, and knowing these from the start can make the way to the top a lot easier. Even though formal mentoring programmes may help, a lot of the information is being shared informally. This informal information sharing may take place anywhere, and spending time with your mentor increases the amount of useful information you will receive. “I hear that a lot of ideas come up when colleagues spend time with their mentor watching football, drinking in a bar, or when they go running together. Even though I enjoy running with my female friends, I would never see myself going for a run with my male seniors.” It is suggested that male colleagues are more likely to bond with their male mentors. Most professors are male, so therefore male PhD students automatically have more access to this informal mentoring.

On the other hand, the awareness of this imbalance tends to improve mentoring. Universities and faculties are setting up more formally organized career-development or training events, sometimes focused exclusively on women. These trainings are perhaps a way to make sure that everyone has access to training and networks. “In my experience, when we give our students the opportunity to present their papers, we have to motivate the female students a bit more compared to the male students.” While these policy measures are meant to close the gender gap, one should be cautious. Some women themselves may not take those opportunities as they feel patronized, and if they do continue their career path with the help of those programmes, they may then feel as if they owe it to this support rather than to their own talent. And their colleagues might share this view, which would emphasize the differences between male and female in the faculty staff.

Furthermore, mentoring is highly dependent on the mentor him/herself. With the high work pressure in the field it is even discouraged by some mentors to have children during certain parts of your career. Even though this could be seen as useful advise, it can discourage researchers to pursue this career path or to postpone maternity more than desirable with respect to fertility. One attendee also mentions that female professors are not as willing to mentor students, as they do not believe that they have the capabilities to do this. In general, women also seem to be less inclined to use (shameless) self-promotion. This further decreases access to and visibility of female role models.

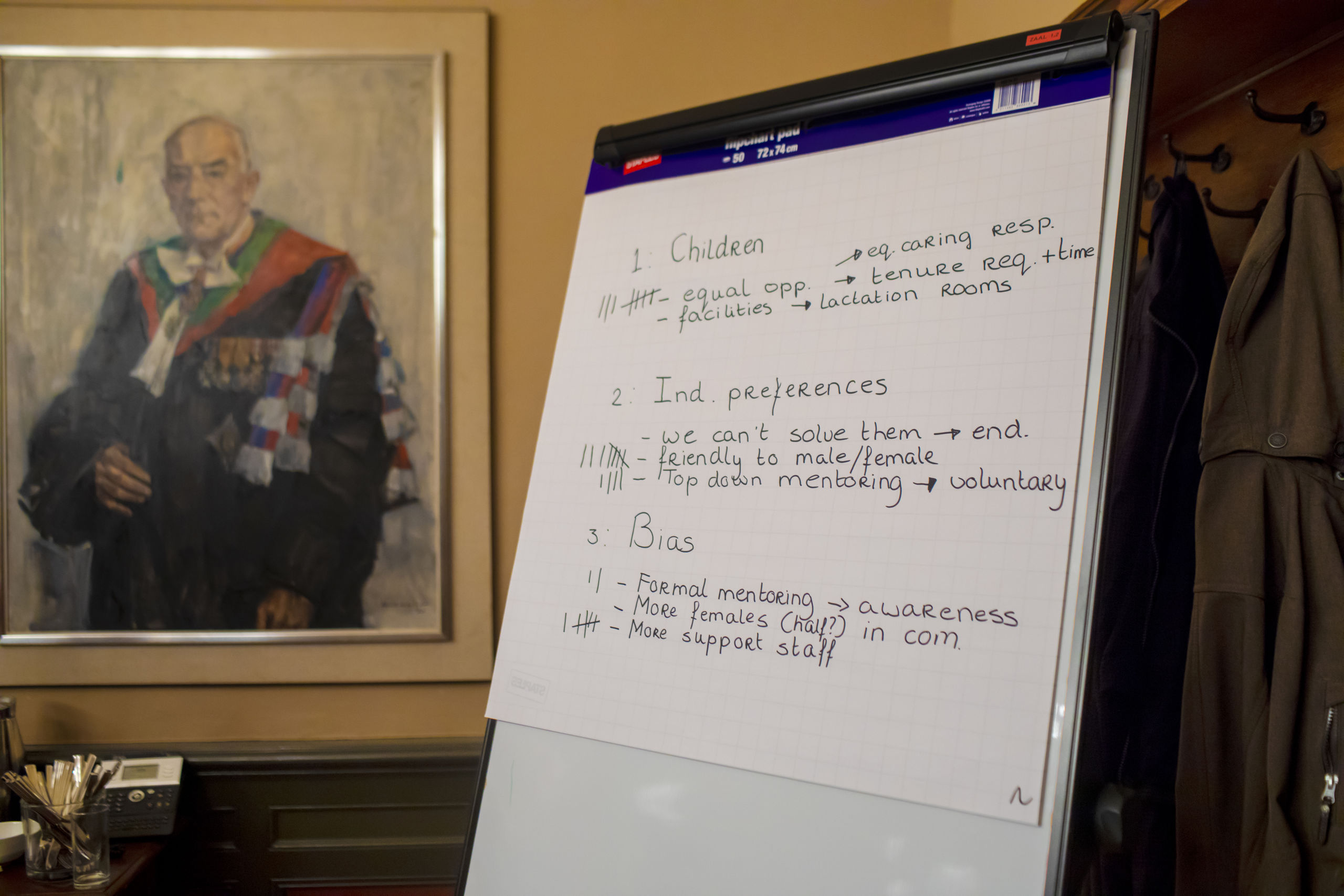

Solutions

Several solutions are put forward at this complex issue. The most popular solutions focus on creating an environment that is attractive to both male and female economists. There is general agreement as to improving the equal opportunities for entering and succeeding during tenure track, by providing incentives to take the same sharing responsibilities or by having more flexible tenure requirements.

One of the more practical solutions mentioned focuses on changing the aggressive culture. It is proposed to hire a moderator for seminars, committees and other events in order to intervene in the discussion, and to make sure that the discussion remains polite and friendly. Heated discussions in itself are not a problem, but one must ensure that everyone participating feels comfortable.

The participants do not fully agree on the best way to mentor new researchers. On the one hand, informal information sharing is seen as the most valuable way to gain information. Encouraging top-down mentoring, at which professors may voluntarily choose to mentor junior researchers, is one way to increase the information being shared. However, it is also pointed out that some young academics might feel lost within this setup, and that therefore formal mentoring is the way to make sure that everyone receives the necessary information.

Conclusions

Even though the number of female professors in economics is increasing, one still very much experiences a gender bias. However, the growing awareness in academia of the low number of female economists is leading to more practical solutions. Extensions for pregnancy in tenure track periods are becoming more common, although they could still be improved as regards flexibility. We should optimize the field of economics given the economics talent we have. That seems like an optimization problem every economist should be interested in.

References

Antecol, H., K. Bedard and J. Stearns (2018) Equal but inequitable: who benefits from gender-neutral tenure clock stopping policies? American Economic Review, 108(9), 2420–2441.

Sarsons, H. (2017) Recognition for group work: gender differences in academia. American Economic Review, 107(5), 141–145.

Auteur

Categorieën