The natural sciences are frequently said to be a veritable male stronghold. The equally striking underrepresentation of women in the field of economics is a less known fact. Still, this may very well have consequences for socio-economic policy.

Women in economics

Why is this article in English?

This article is part of our English publication ‘Women in Economics’. This dossier is in English because English is the main language of the economics and business faculties in the Netherlands, so an ESB dossier about the people who work there should be in English.

This article was originally published in Dutch in March 2018. The Dutch version can be found here.

In brief

– The academic field of economics has the lowest number of female full professors.

– Women, on average, have a different perspective of the desirable role of markets and governments.

On September the 19th, the economic section of ING published the Economists’ compass for public finances (ING, 2017). In this publication, eleven Dutch star economists set out their recommendations for the public budgetary policy. All of the ‘stars’ were men. In late August, De Telegraaf newspaper ran an ‘economists survey’, in which twenty prominent Dutch economists were asked to list their main policy priorities in light of the formation of the new government. Two of them were women.

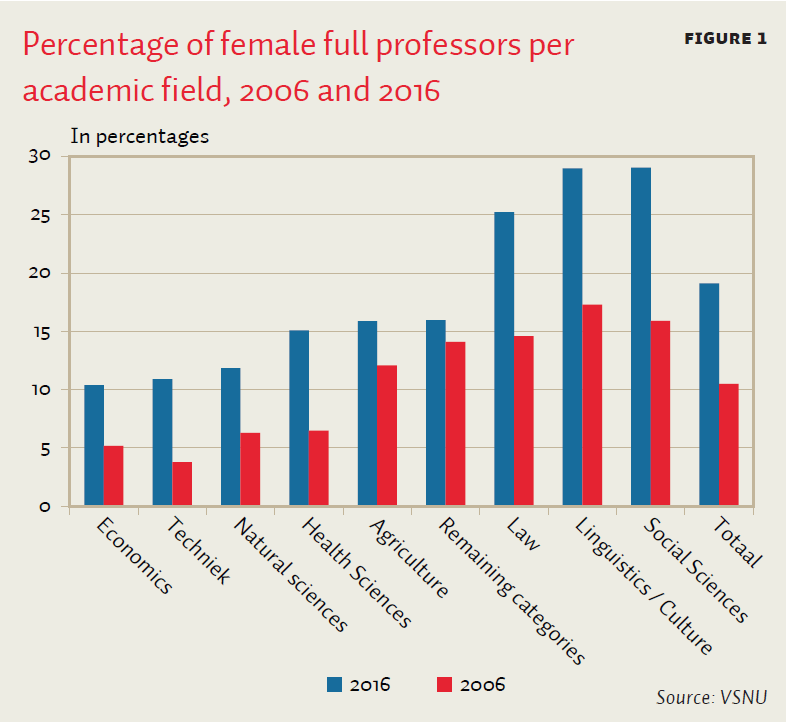

These examples seem a fair reflection of female representation at the top of Dutch economic sciences. At Dutch universities, in 2016, 10.4 percent of the full professors in the economics departments were women. Although that is twice as many as in the previous decade, economics has in the meantime been overtaken on this score by the field of engineering, and in 2016 had the lowest number of female full professors of all scientific fields (see figure 1). Women are less likely to obtain a full professorship in economics than in any other science; see box 1.

When considering the number of citations – another indicator of academic impact – the conclusions regarding female representation in the science of economics are not much more encouraging. The Polderparade (Maasland, 2014), a list of the most frequently cited economists in Dutch and Flemish journals, in 2014 only included the name of one woman, to wit Barbara Baarsma, taking the 30th place.

Also in international citation rankings, female economists are conspicuous by their absence. In the academic publications of RePEc/IDEAS, there are two women featuring in the top 100 of the world’s most cited economists: Carmen Reinhart (Harvard), ranking 11th, and Asli Demirgüç (World Bank), ranking 60th. There is no sign of any marked convergence – if we just look at the articles published over the last decade, only five women make it to the top 100.

Box 1: Insufficient career advancement

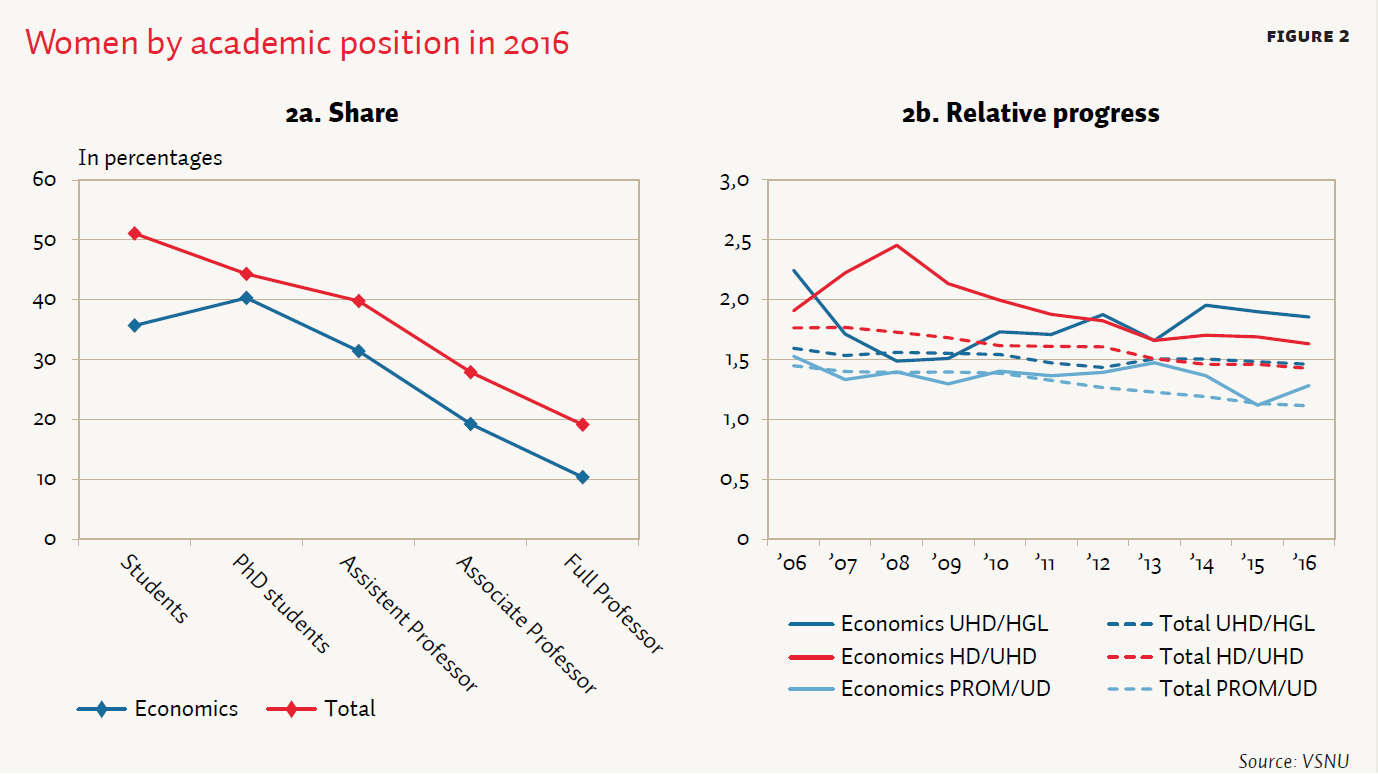

Of the PhD students in economics, 40 percent are female (see figure 2). This is comparable to the average in the overall fields of science, and it is considerably more than the 28 percent of female PhD students within the various fields of natural sciences and engineering. To gain some insight into the bottlenecks for women in their advancement towards higher academic positions, the VSNU has constructed the ‘glass-ceiling index’ (GCI). The GCI is computed by dividing the percentage of women in a career-stage category by the percentage of women in the next category in the same year. The career-stage categories are PhD student (PROM), assistant professor (UD), associate professor (UHD) and full professor (HGL). An index larger than one indicates a relatively limited progress of women into the next category, in comparison to men. Figure 3 shows the GCI for the academic category of Economics, during the period 2006–2016, and the aggregate over the various academic fields.

The GCI for all scientific fields is at every transition – from PhD student to assistent professor, from assistent professor to associate professor, and from associate professor to full professor – larger than one. Since 2006 the GCI has been decreasing in all scientific fields, and to a lesser extent also in economics. This signifies an improvement in the advancement opportunities for women. However, advancement in economics is lower than the average in other fields at any of the career stages, and particularly at the transition to a full professorship. Female associate professors – representing 31 percent of the total of associate professors in Economics – are faced with the fact that it is almost half as likely they will attain a full professorship than it is for their male counterparts.

Potential consequences

Women’s meagre representation in the field of economics might very well have negative implications for the quality of economic research. Various papers show that teams with a diverse composition (in regard to both gender and cultural background) perform better (Woolley et al., 2010; Hoogendoorn et al., 2013). There are indications that this conclusion also holds in academia. Campbell et al. (2013) assert that, within the field of Ecology, peers were more likely to favourably rate scientific contributions when these had been written by a mixed team of authors (male/female) than when this was not the case, and that the number of citations would consequently be 34 percent higher. Female underrepresentation among authoritative economists can also have consequences for the manner in which socio-economic policy – pertaining to a range of subjects, such as the labour market, trade policy or the financial sector’s regulation – is nurtured and steered by academic input. This would be the case if women, in comparison to their male colleagues, differ in their perception of economic issues.

May et al. (2013) discovered that male and female members of the American Economic Association (AEA) indeed differed in their opinions on economic policy issues, also after the correction for age differences and work environment. They even established that gender was the only relevant factor that led to statistically significant differences with regard to the perception of the desirable degree of government intervention in the functioning of markets.

On average, male AEA members think significantly more often than their female counterparts that in the United States (US) and Europe government regulation is too extensive. Moreover, they also markedly differ in their opinions on redistribution: women far more frequently support the notion that, in the US, income distribution should be more equal and that a more progressive tax system would be desirable. Female respondents also notably more often thought that the US should combine a further liberalisation of trade with labour standards aimed at protecting workers. Men more frequently believed that a high minimum wage would lead to more widespread unemployment.

The same authors replicated their research among 1,000 doctoral economists affiliated with eighteen European universities (May et al., 2018). Here, too, women on average had a stronger preference than men for government regulation as to matters like the labour market, migration and international trade. The largest difference in responses between male and female economists was recorded in response to the statement ‘Further regulation of the labour market will lead to inferior economic outcomes’. An interesting extension of the American research paper focussed on the perceptions regarding environmental protection. Female economists were on average more likely to agree with the statement that government intervention was necessary, whereas men overall disagreed. The divergence in responses was statistically very significant.

The authors conclude that female economists are more inclined to accept government intervention as a strategy to mitigate forms of social injustice, whereas men focus on the risks associated with the distortive effects of government intervention. They claim that, as a consequence, in the public debate on economic issues – which is dominated by male economists – a stronger emphasis is placed on the costs of government intervention relative to its benefits.

Conclusion

In the Netherlands, male economists dominate the discussions on matters of socio-economic policy. Economic experts, as presented by ING and De Telegraaf, among others, are almost exclusively men. This is also true of the economists most frequently cited in popular academic publications and of economics professors.

Research indicates that male and female economists in the US and several European countries distinctly differ in their views as to the desirable role of markets and governments. Notwithstanding the fact that the results of the European research contribution are not specified according to the respondents’ country of origin, it seems plausible that these differences also exist among Dutch economists.

Of course, there are several women outside the science of economics – politicians, policymakers, and for instance the director of the CPB (Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis) – who wield a great deal of influence over the socio-economic policies pursued. Nonetheless, a shift towards a more equitable representation of men and women in economics may lead to policy issues being viewed from a broader perspective, and the consideration of a more balanced set of arguments in determining the optimal role of markets and regulation in the economy.

References

Campbell, LG., S. Mehtani, M.E. Dozier and J. Rinehart (2013) Gender-heterogeneous working groups produce higher quality science. Plos One, 8(10), e79147.

Hoogendoorn, S., H. Oosterbeek en M. van Praag (2013) The impact of gender diversity on the performance of business teams: evidence from a field experiment. Management Science, 59(7), 1514–1528.

ING (2017) Worstelen met de weelde? Economen bieden kompas voor overheidsfinanciën in goede en slechte tijden. ING Economisch Bureau, September.

Maasland, E. (2015) Polderparade 2014. TPEdigitaal, 8(4), 48–58.

May, A.M., M.G. McGarvey and R. Whaples (2013) Are disagreements among male and female economists marginal at best?: a survey of AEA members and their views on economics and economic policy. Contemporary Economic Policy, 32(1), 111–132.

May, A.M., M.G. McGarvey and D. Kucera (2018) Gender and European economic policy: a survey of the views of European economists on contemporary economic policy. Kyklos, 71(1), 162–183.

Woolley, A.W., C.F. Chabris, A. Pentland et al. (2010) Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science, 300(6004), 686–688.

Auteurs

Categorieën