Boundaries are increasingly blurring, whether that is between countries, between sectors, or between producers and consumers. As boundaries blur, we should consider redesigning them. This article explores the blurring of boundaries through globalisation, digitisation and sustainability.

Societies are increasingly intertwining. Globalisation, digitisation and climate change cause boundaries to blur. Globally, billions of interactions take place on a daily basis. Goods, capital and people are increasingly mobile. Communication networks, power grids and value chains interlink, causing news, energy and data to move rapidly around the world.

Summary

– Allow international acquisitions within a level playing field, in terms of state aid and reciprocal market access.

– Sharing data should be the point of departure, as a single data set often has a great variety of uses.

– Taking the lead in sustainability is possible while maintaining competition.

Dutch original

This article is translated from Dutch. The title of the original is Scherp zijn bij vervagende grenzen.

These developments bring a new dynamism. International capital flows have increased exponentially, with new players entering the stage. For the first time, the outflow of Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) exceeds its inflow. Data change the way in which companies produce. The world’s largest provider of accommodations (Airbnb) does not own any property and a key retailer (Amazon) hardly owns any stores. Given global climate agreements, it is no longer a question whether we should take action, but at which pace we should do so.

This dynamism puts pressure on society and gives rise to new questions. It forces us to rethink how we can best safeguard our public interests. On the other hand, overreacting as public interests come under pressure can hamper growth and dynamism. We should strike the right balance.

As boundaries blur, we should consider redesigning them. Global value chains, for instance, raise questions about whether Dutch companies are responsible for working conditions or environmental damage abroad. The rise of consumers who also produce (so-called prosumers) forces local governments to rethink the legal distinction between landlords and tenants. People working in the gig economy are usually neither employee nor freelancer. This development gives rise to a debate on the applicability of our labour laws.

It is key to both safeguard public interests and maintain dynamism at the same time. This process requires constant recalibration. In this article, I tackle questions that arise as a result of globalisation, digitisation and sustainability. How can we uphold our open attitude towards foreign investment? How should we handle data as a new production factor? And how can we strengthen our competitiveness, while leading the way in sustainability?

Globalisation

In recent decades, economic relations between countries have intensified. FDI has more than tripled worldwide over the last fifteen years (UNCTAD, 2017). In a globalised world, companies pick the best locations for their investments. Open economic relations are in the interest of the Netherlands. We are a key recipient of FDI (€ 773 billion in 2016) but also a large investor abroad (€ 1,322 billion in 2016). The Netherlands is the world’s third-largest private investor, after the United States and China (UNCTAD, 2017). Our open economy has given us access to markets all over the world, and has brought jobs and prosperity at home (Statistics Netherlands, 2017).

However, the global scene is changing. Emerging economies such as China, India and Indonesia are surpassing western economies in growth and their influence is growing as a result. In the coming decades, China will overtake the United States as the world’s largest economy (PwC, 2017). The country’s economic model is driven by a government that more actively intervenes in the market, based partly on geopolitical considerations. Traditional global partners, such as the United States and the United Kingdom, are also reorienting themselves and increasingly put their own interests ahead of those of other countries. These developments undermine trust in the reciprocal nature of our trade relationships.

The changing global scene asks us to reconsider our strategy. The European Commission has thus far limited itself to addressing national security and public order in so-called vital sectors. Our society greatly depends on products and services supplied by these sectors, such as telecommunications and energy. In order to limit risks for the economy and society, it is crucial that their operation is safeguarded. In the US, CFIUS assesses the potential impact of acquisitions in vital sectors on national security. As a result, an acquisition can be blocked unless it is restricted to certain less vital activities. The operation of vital sectors in Europe is often already safeguarded at the national level, which raises the issue of subsidiarity within the European Union.

European policy should focus on achieving a level playing field, not only among European players but also among firms from outside the EU. The EU has set the terms on its internal market in a regulatory framework that prohibits states from intervening in companies and from providing state aid that distorts competition. This policy prevents companies from competing with tax payers’ money. That regulatory framework applies to a far lesser extent to firms from third countries. As a result, they can enter the European market with state aid. The European Union hardly imposes restrictions and is readily accessible to FDI. Conversely, this access is limited in other countries, such as the United States and India. Establishing an operation in China even requires at least half of the company to be owned locally. As a result, European players face barriers when they want to invest.

European companies experience an uneven playing field, both on their internal market, due to the possibility of state aid provided by third countries’ governments, and abroad, as a result of restricted market access. This is all the more pressing for economic sectors of strategic importance, which are drivers of innovation, given their essential knowledge base. Regional clusters, such as in Eindhoven with its Technical University, ASML and Philips, are key sources of innovation and competitiveness. So far, however, European governments’ ability to interfere in acquisitions outside of vital sectors is extremely limited. A case in point was the German government being unable to prevent the Chinese acquisition of innovative robot manufacturer KUKA.

Here, blurring global boundaries require new rules. The regulatory framework within the European Union to tackle government interference and state aid in companies must be applied more broadly, so as to include players from third countries. In the event that there is any suspicion of government interference, the European Commission should be authorised to assess whether state aid was given. This can be done by inspecting the accounts of the acquiring party and then taking the necessary measures.

However, an extension of the framework alone is insufficient. Reciprocity should become a more central principle of European trade policy. When parties from third countries want to invest in Europe, these countries should also allow acquisitions by European parties. When third countries fail to comply, this should have consequences for certain investments and acquisitions. In addition, in its trade policy, the European Commission can make reciprocal market access a more prominent requirement in trade and investment agreements. If so, open borders and a level playing field can continue to go hand in hand.

Digitisation

Boundaries between sectors, as well as between producers and consumers, are increasingly blurring as a result of digitisation. Take Facebook, for example, which no longer appears to be only a tech company that offers a platform but increasingly comes across as a media company that should accordingly take responsibility for the content which it offers. Platforms can direct and exclude companies and consumers, and they increasingly appear to provide a public service.

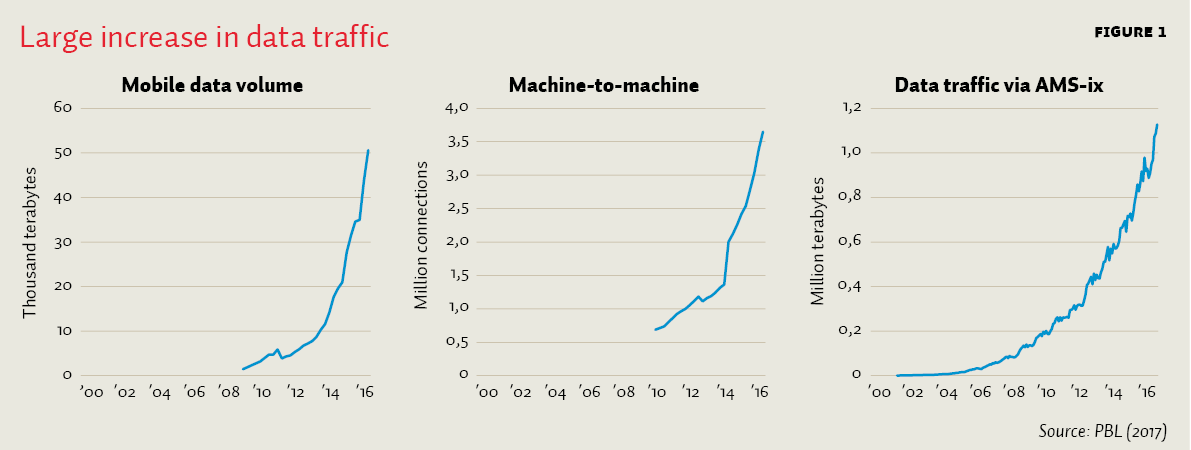

The current wave of technological development is largely driven by data as a new production factor. Computers and devices are increasingly interconnected globally. As data storage is becoming cheaper and the price of computing power and sensors has fallen, data collection and data analysis can take place at an ever-increasing scale (Figure 1). That increase continues at an exponential rate, with the amount of data growing by around thirty per cent annually (Hilbert, 2015). The data economy is expected to represent roughly four per cent of the European economy by 2020 (IDC, 2017). The Dutch economy by comparison currently makes up 4.7 percent of the European gross domestic product.

With the rise of data, new questions arise. Unlike other immaterial goods such as ideas, data are presently not subject to legal property rights. Economic transactions are usually assumed to require clear property rights. These guarantee exclusive use and revenues, which give incentives for investment and innovation. However, exclusivity hampers third-party use, and can also withhold innovation and new applications. This dilemma also applies to data.

Data, however, have a number of special properties. A single data set can potentially serve a great variety of uses, which do not necessarily compete; for example, improving and developing products, services, processes, research and supervision. Some data applications only become clear after data become accessible. By making data more widely available, their innovative use may increase, as may their contribution to society.

To this end, sharing data should be the new standard, moving from “exclusive access to data, provided that…” to “sharing data, provided that…”. Exclusive access can currently give rise to market power. For instance, car manufacturers can favour specific service stations and dealers by giving them exclusive access to in-vehicle data, such as information on repairs and maintenance. Enforcing shared data would increase competition and reduce market power. The same notion applies to data gathered by internet companies such as Google and Facebook (Tirole, 2017; Van Oosten, 2017). For instance, one can think of data used for search engine optimisation, such as users’ clickstream following certain search queries. By increasing access to such anonymised clickstream data, other parties in different markets can use them for further innovation. At the same time, a strong concentration of large internet companies on these markets can be avoided (Prüfer and Schottmüller, 2017). One can think of the markets for digital maps, retail and, in the future, autonomous cars.

An important principle is that citizens should be in control of data which can be traced back to them, so-called personal data. With the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which will enter into force on 25 May 2018, consumers will receive extensive rights over these personal data. The GDPR includes a new data portability right, allowing information to be taken along to other parties. This improves not just citizens’ control of their data, but it potentially increases competition and innovation as well, since users are free to move their information to competing companies. For instance, music playlist data could be transferred to competing providers of streaming services. As a result of this legislation, consumers are provided with a “data-sharing right”. A type of portability right for non-personal data could also offer such advantages.

Any of these advantages of sharing data must be balanced against their possible effects on investment incentives, costs of implementation, cybersecurity and privacy. The approach taken in the financial sector is interesting in this regard. Here, compulsory data-sharing has also been introduced in order to stimulate innovation. Within the European Payment Services Directive (PSD2), banks have to share account information with competitors when individual consumers approve. This directive introduces market opportunities for new players and may lead to new products for payment transactions.

Given privacy concerns, compulsory sharing of large-scale personal data is undesirable. However, this objection can be solved if data are processed to prevent the possibility of tracing them back to a person. As a data hub, Netherlands Statistics (CBS) already employs a comparable method. It could be supervised by a public agency, monitoring the sharing and anonymisation of the data. In order to preserve incentives for data collection, a fee for the data could be in order. Certain networks currently face a similar situation, where the rates to access KPN’s landline telephone network are determined by the Netherlands Authority for Consumers and Markets, for instance. Given the cross-border nature of data collection, compulsory data-sharing requires European regulation.

It should be noted that market parties are often open to voluntarily sharing data, but that they are inhibited by high transaction and coordination costs. Through policy, government can play a role to reduce such costs; for example, by clarifying current laws and regulations or by contributing to the development of standard contracts, agreements systems and codes of conduct. Best practices are emerging from health care, logistics and the industry. An initiative in the Port of Amsterdam aims to use shared data in order to improve safety and efficiency in inland waterway transport. The health care industry seeks to gather data from various sources in a safe and secure e-health environment (MedMij).

Sustainability

Major sustainability issues also do not abide by national borders. They cannot be solved by one country alone. The Netherlands is responsible for half a percent of global CO2 emissions, which is a modest contribution to climate change on a global scale. Limiting global warming, as well as solving many other environmental issues, therefore requires international agreements. Being a front-runner to such international agreements can weaken one’s international competitiveness in the short term, but it does make economic sense in certain cases.

Within the Netherlands, market actors and civil society increasingly find each other in sustainability initiatives. Clear international road maps to higher product and production standards are usually lacking here, despite global agreement on the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). As it is uncertain whether other countries will strive for the same standards, taking a front-runner position here may pose an economic risk .

Dutch society still asks for higher domestic standards. The coalition agreement of the current government contains a number of proposals on this matter. Where parties compete largely on prices, reining in competition seems a logical step to promote sustainability. Eliminating competition is often unwise, however, as it can cause interests in the sectors or industries shielded from competition to become ingrained.

“The Chicken of Tomorrow” (“Kip van Morgen”) serves as an illustration. Designed to have had a better and longer life than most poultry sold in Dutch supermarkets until 2013, civil society pushed supermarkets, producers and processors to cooperate in realising a more sustainable chicken. The premise was that only in the absence of competition would parties in the value chain collectively switch to a more sustainable chicken. The Dutch competition authority, however, decided that this was a violation of the Dutch Competion Act (Mededingingswet). The ruling did not halt efforts for a better chicken. Many supermarkets nowadays impose higher standards for their chicken, making today’s chicken more sustainable than “the chicken of tomorrow”. In the end, the forces of competition together with a push from civil society led to a more sustainable chicken in Dutch grocery stores. It should be noted, though, that Dutch poultry farms continue to apply lower standards for their exports to foreign markets.

Markets cannot always provide sustainable products. If this is the case, and societal preferences for higher standards are widely shared, higher standards should be set by laws and regulations rather than by sectoral agreements curbing competition. Only then can the loss of competition on the one hand be publicly traded off against the potential gains in sustainability on the other hand. The legislative proposal “Sustainability Initiatives” (Ruimte voor duurzaamheidsinitiatieven) offers a solution. It will facilitate collaboration between companies in the value chain but ensures public oversight of these agreements (Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, 2017).

Being a sustainable front-runner by raising national standards makes economic sense when higher product standards are emerging internationally. In time, the international playing field will level out again. For example, the Circular Economy Package (European Commission, 2015) represents a movement within Europe towards stricter standards for a circular economy in terms of recycling and design. The starting position of the Netherlands here is good, as our current recycling efforts already exceed European requirements. Even higher domestic standards for recycling will offer opportunities to our business community on the domestic market, helping us to become a front-runner in this European movement.

Conclusion

In sum, we see a wide international dynamism which blurs boundaries. As such boundaries blur, we should consider redesigning them. To this end, we should direct our efforts to achieve an international level playing field. The regulatory framework that we have agreed on within Europe should also apply to firms from third countries, including that on state aid. Only then can we maintain our open attitude towards FDI. We should publicly enforce higher sustainability standards where these match an international movement, but without eliminating competition. By doing so, we can set our goals to achieve a more sustainable economy. Data have the potential to put forth a new wave of innovation. We should therefore introduce data-sharing as a leading principle, in order to stimulate innovation, rather than legally protecting data with property rights as is customary with other immaterial goods.

At the same time, we must prevent means and end from conflicting. As public interests come under pressure, we should be hesitant to hastily adopt new regulations that curb this dynamism. Our new answers should rather be formulated to maintain dynamism.

References

Netherlands Statistics (2017) Internationaliseringsmonitor 2017-IV. Waardeketens.

European Commission (2015) Closing the loop – An EU action plan for the Circular Economy. Publication COM (2015) 614.

Hilbert, M. (2015) Quantifying the data deluge and the data drought, 1 April 2015. Report retrieved from ssrn.com.

IDC (2017) European data market SMART 2013/0063. Final Report. Retrieved from datalandscape.eu.

Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy (2017) Memorie van toelichting ruimte voor duurzaamheidsinitiatieven. Retrieved from www.internetconsultatie.nl.

Oosten, R. van (2017) Jean Tirole: een vurig pleidooi voor de waarde van economen. ESB, 102(4756), 566–569.

PBL (2017) Mobiliteit en elektriciteit in het digitale tijdperk: publieke waarden onder spanning. PBL Report, 1874.

Prüfer, J. and C. Schottmüller (2017) Competing with big data. TILEC Discussion Paper, 2017-006. Tilburg: TILEC.

PwC (2017) The long view: how will the global economic order change by 2050? London: PWC UK.

Tirole, J. (2017) Economics for the common good. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

TNO (2016) Data deling zorgt voor veilige en efficiënte binnenvaart. News item retrieved from www.tno.nl.

UNCTAD (2017) UNCTADStat Data Center. Geneva: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development.

Auteur

Categorieën